India's first & foremost horse racing portal

All About Equines

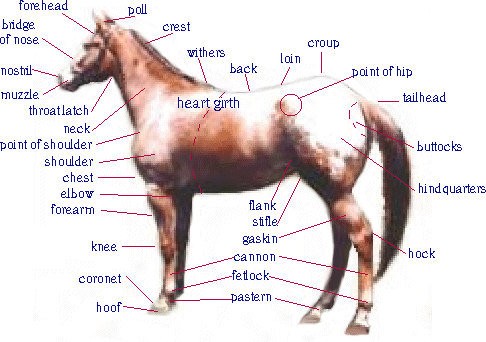

The Points of a Horse

| S.No | Points | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Poll | The poll is the bony prominence lying between the ears. Except for the ears, it is the highest point on the horse's body when standing up. |

| 2 | Forelock | The forelock is the hair that covers the forehead and that grows from the poll area. It must not be confused with the fetlock. |

| 3 | Withers | The withers is the prominent ridge where the neck and back join. At this ridge, powerful muscles of the neck and shoulder attach to elongated spines of the second to the sixth thoracic vertebrae. The height of the horse is measured vertically from the withers to the ground, because the withers is the horse's highest constant point. |

| 4 | Back | The back extends from the base of the withers to where the last rib is attached. |

| 5 | Loin | The loin (or coupling) is the short area joining the back to the powerful muscular croup (rump). |

| 6 | Croup | The croup (rump) lies between the loin and the tail. When one is looking from the side or back, it is the highest point of the hindquarters. |

| 7 | Dock | The dock is the bony portion of the tail that tapers to a point about one-third of the way down the tail. |

| 8 | Chest | The cheat is encased by the ribs, extending from between the forelegs to the`s. |

| 9 | Breast | The breast is a muscle mass between the forelegs, covering the front of the chest. |

| 10 | Flank | The is the area below the the loin, between the last rib and the massive muscles of the thigh. |

| 11 | Shoulder | The point of the shoulder is a hard, bony prominence surrounded by heavy muscle masses. It is approximately level with the intersection of the lower line of the neck and body. |

| 12 | Elbow | The elbow is a bony prominence lying against the chest at the beginning of the forearm. |

| 13 | Forearm | The forearm extends from the elbow to the knee. |

| 14 | Chestnut | The chestnuts are horny growths on the insides of the legs, located approximately halfway down. |

| 15 | Knee | The knee is the joint between the forearm and the cannon bone. |

| 16 | Cannon Bone | The cannon bone (or shin), as it's called when in the foreleg, lies between the knee and the fetlock, and is visible from the front. |

| 17 | Flexor Tendons | The flexor (back) tendons run from the knee to the fetlock and can be seen lying behind the cannon bone. |

| 18 | Fetlock | The fetlock is the joint between the cannon bone and the pastern. |

| 19 | Ergot | The ergot is a horny growth at the back of the fetlock, hidden by a tuft of hair. |

| 20 | Pastern | The pastern extends from the fetlock to the top of the hoof (coronet) |

| 21 | Coronet | The coronet is a band around the top of the hoof from which the hoof wall grows. |

| 22 | Hoof | The hoof refers to the horny wall and sole of the foot. The foot includes the horny structure and the pedal and navicular bones, as well as other connective tissues. |

| 23 | Heels | The heels are the bulbs at the back of the hoof and while horny in texture, they are often softer than normal hoof wall. |

| 24 | Point of Hip | The point of hip is a bony prominence lying just forward below the croup. This is not the hip joint. |

| 25 | Stifle | The stifle is a join at the end of the thigh corresponding to the human knee. |

| 26 | Gaskin | The gaskin (second thigh) is the region between the stifle and hock. |

HOCK - The hock is the joint between the gaskin and the cannon bone. The bony protuberance at the back is called the point of hock. It may be easily injured, especially when the horse kicks.

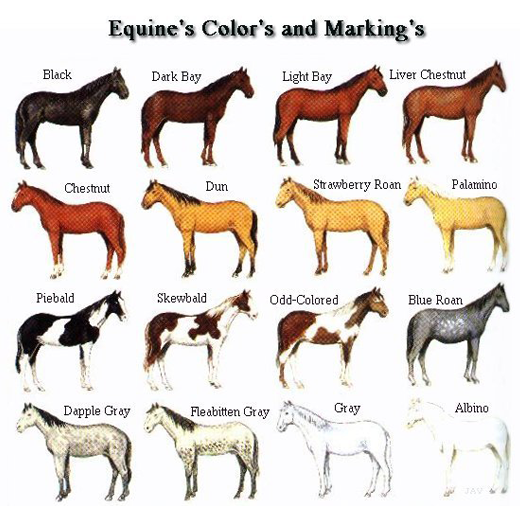

Equine Colors - How A Horse Gets Its Color

Equine coat coloring is controlled by numerous genes acting in combination to produce a multitude of variations in pigmentation. These genes, which are inherited are located on paired structures known as chromosomes; the modern horse has 64 chromosomes, half of which are inherited from the sire, the other half from the dam. Some genes are dominant, others are recessive. For example, in horses, chestnut is recessive, all other colors, bay is dominant to black. The dominant greying gene can result in horses which are born with a dark coat turning progressively more grey as they grow older. This is especially noticeable in the Lipizanner, whose foals are born dark and, with rare exceptions, turn grey as they mature.

Coat color and markings developed over millions of years to give the horse the best camouflage possible for the area the horse lived. The most primitive horse and pony color is Dun (yellowy beige) with black points (points being mane, forelock, tail, and lower legs). Old stories tell of "good" and "bad" colors in horses. Chestnut horses were supposedly hot tempered, black as being nasty and lacking stamina, bay and brown dependable, and so on. The truth is that color has no bearing whatsoever on temperment or performance ability.

The only exception to this are horses who have pink skin under white hair (some white haired horses have dark skin underneath). These horses are much more susceptible to weather than others, because pink skin lacks the strengthening substance melanin which is responsible for skin and hair color. The pink hue comes from blood circulating through the colorless skin. Because the skin is less resistant to sun and wet, and hence bacteria, it becomes more easily infected with skin diseases, sunburn, and allergies.

True Albinos have no coloring agents in their bodies. They have pink skin, white hair, and pink eyes. Some so-called albinos have blue eyes, but this is not true albinism, as blue is a coloring matter. Blue eyes are not all that common in horses, however, and where it does occur often only one eye is blue, called a wall eye. There is no evidence that wall eyes see less well than dark eyes, but albinos with pink eyes (due to blood circulating through the iris) are known to have poorer sight.

The following are some basic colors of the horse:

| S.No | Colors | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | BAY | (Varying from reddish to yellowish) That always has a black mane, tail, and black legs, referred to as points. |

| 2 | CHESTNUT or SORREL | A chestnut horse is a horse whose coat is basically red. Varies from a pale golden color to a rich, red gold. The mane and tail are normally the same color as the body, but may be lighter or darker than the body. If the mane and tail are lighter in color than the body, the horse is referred to as having a flaxen mane and tail. Thoroughbreds of this color are called chestnut; quarter horses are called sorrel. The darkest of chestnut shades is referred to as a "Liver Chestnut" and usually has a flaxen mane and tail. |

| 3 | BROWN | Dark brown or nearly black. If ANY brown hairs are visible on the face or body, the horse is brown rather than black. Many brown horses are mistakenly called black. But a close examination of the hair around the muzzle and lips will soon confirm if the horse is truly black or brown. |

| 4 | BLACK | All hairs are black, although white markings may be found on the face and lower legs. A black horse has black eyes, hooves, and skin. If there are tan or brown hairs on the muzzle or flank, this horse would be referred to as a seal brown |

| 5 | DUN | Yellowish or tan with similarly colored mane, tail, and legs. A Dun has a dark "Dorsal" stripe running down the back. |

| 6 | BUCKSKIN | Same as dun, but legs, mane, and tail are black. A Buckskin may or may not have the dorsal strip running down the back. |

| 7 | PALAMINO | Golden, with flaxen or whitish mane and tail. |

| 8 | GREY | A mixture of black and white hairs throughout. The coat varies from light to iron (very dark). The skin is black. A "Fleabitten Grey" coat is flecked with brown specks. A "Dappled Grey" has a light grey base coat with dark grey rings. |

| 9 | WHITE | Most so-called white horses are gray. The only true white horse is an albino. If the horse at any time of its life has had hairs of any color other than white, it is probably a gray. |

| 10 | ROAN | Black or brown with a sprinkling of white hairs (blue roan), or chestnut with a sprinkling of white (strawberry roan). |

| 11 | SPOTTED | More or less circular patches of hair in a different color than the base coat. Distributed over the body in various sizes and amounts |

Equine Coats

Horses and Ponies grow two coats per year. The summer coat is short and sleek to allow efficient heat loss in hot weather, when protection against cold and wet is not so critical; the winter coat is longer and thicker (because the longer hairs overlap), and protect the animal against wind by trapping a layer of warm air next to the body to insulate it, and against the wet.

In native, cob and cold-blood breeds, the winter has large numbers of longer hairs to help water drain off more efficiently. Such breeds also have long hair, called feathering, around the fetlocks to help protect against mud and wet.

Some pony breeds, particularly those from northern climates, have a double coat in winter, with long outer hairs to keep out the wind and rain, and shorter under-hairs for extra warmth and protection. Their manes and tails are often wiry and thick for the same reason.

The skin of all breeds produces natural grease to help lubricate the skin and hair and provide protection against the rain and, to a very small extent, flies. The skin itself has an outer layer of dead tissue which is gradually shed as fresh cells come to the surface to replace it. The outer layer ensures that the skin is protected and is not over- sensitive. The shed flakes are seen in an ungroomed animal as dandruff.

In the natural state, this grease and dandruff does not become excessive, and is left on the skins coats of domesticated horses that spend a lot of time in pasture, to help give protection. However, stabled animals have grease and dandruff removed by body brushing, to ensure that the skin is clean and stimulated, and able to work efficiently at excreting, through sweating, the waste products of exercise and a concentrated diet.

Horses groom themselves in the wild in a rough and ready way. Mutual grooming, where horses go along each other's back with the top teeth, helps dislodge and discourage parasites and is enjoyed by all. Horses also stimulate their skins by rubbing against hedges and trees, and by rolling.

Casting the Coat

Horses cast (change or molt) Their coats in spring and autumn and tend to look a little rough, particularly in autumn. There is an old saying that no horse looks its best at blackberry time, and it's true. The hair comes out at intervals-the horse will cast a little and grow a little, cast a little and grow a little, until after a month or two the new coat will be complete, or "set".

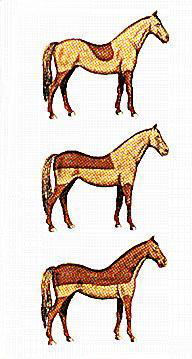

Clipping the Coat

Clipping helps prevent excessive sweating during winter. The type of clip depends on the horse's workload, constitution, and how you keep it. The hunter clip (top) is only for for very hard working stabled animal. The blanket clip (middle) suits moderate to hard-working horses stabled or kept on the combined system. The trace clip (bottom) is suitable for horses or hardy native ponies doing light work, and kept out.

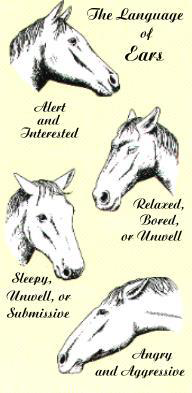

The Language of Ears

The position of the ears is one of the most important indicators of a horses mood and intentions. Ears pricked forward are a sign of alert curiosity and good mood. Ears tucked back are often a sign of relaxation, or even boredom. They may also be a sign that the horse is unwell. The ears pressed flat against the head are a classic sign of bad temper and aggression. It can also signify that the horse is feeling stressed. When the ears flop to either side, it may be a sign of sleepiness or sickness. It is also a typical sign of submission to a more dominant horse.

How Horses Hear

Horses are very sensitive to sound, and can hear high- and low-pitched noises that humans are unable to pick up.

The pinna, or funnel part of the ear, picks up the sound waves and directs them down inside the the head where a network of bones and chambers together with the eardrum transmit and amplify them for special nerves to pick up. These nerves in turn transmit these messages to the brain, which translates the sounds into meaning if they are familiar, or alerts the horse to something strange in its environment if they are not.

A horse does not automatically panic at unfamiliar sound; it will pay attention to it and remember it. If something happens at the same time as the sound, it will, in future, associate the happening with that sound, and this is important part of training and learning.

Horses' hearing is sharper than that of humans; they can hear things like other horses calling, car engines (which they can tell from each other) and doors opening, before a person can pick them up and from much farther away. Horses that are boarded out, for example, soon come to recognize their owners' car engines and associate the noise with the appearance with that particular person. They will often pick up on a sound long before the staff in the stable.

Horses are extremely sensitive to the nature of a sound and it's volume. There is never any need to shout at a horse unless it is a very dominate animal either attacking or really pushing it's weight around, in which case volume can help get the better of it. Tone of voice is usually more effective than volume; a cross growl when a horse is doing wrong, and an up-and-down, pleased tone for praise.

Screaming, and screeching often frighten horses, whereas soft momotones calm them down. However, some sounds which might be thought to frighten them, such as blasting in a quary or police sirens, do not always do so.

Horses are as agitated by constant, raucous sound as humans are. In racing stables, for instance, the best trainers insist on a quiet period during the afternoon after morning work, grooming and the midday feed, so that the horses can lie down and rest or have a sleep.

Some horses prefer a busy atmosphere where they can see and hear what is going on around them, and others like peace and quiet. It is important to watch your horse and try to tell by its behavior and expression which category it falls into. If it seems slightly (or very) tense, its ears flicking around a lot, not resting much during the day, it could be that there is to much noise going on for its liking.

The best thing a person could do for their horse is; getting to really know your horse, watch it's every mood, pay attention to the subtle movements in its ears, and really listen to your horse. It will let you know how it's feeling, if you just listen.

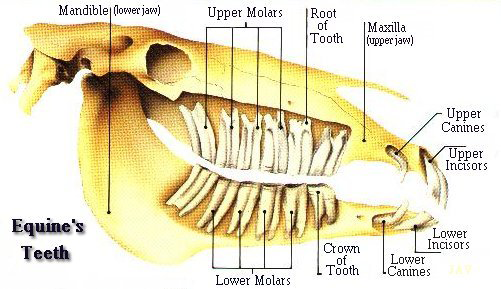

Equine Teeth

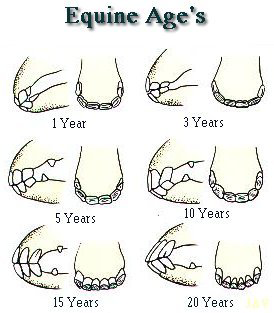

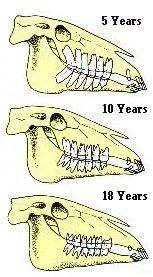

Determining the age of horses by inspection of the teeth is one that takes some skill. It can be developed to a considerable degree of accuracy in determining the age of young horses. The probability of error increases as age advances and becomes a guess after the horse reaches 10 to 14 years of age. Stabled animals tend to appear younger than they are, whereas those grazing sandy areas, such as range horses, appear relatively old because of wear on the teeth.

The position of the ears is one of the most important indicators of a horses mood and intentions. Ears pricked forward are a sign of alert curiosity and good mood. Ears tucked back are often a sign of relaxation, or even boredom. They may also be a sign that the horse is unwell. The ears pressed flat against the head are a classic sign of bad temper and aggression. It can also signify that the horse is feeling stressed. When the ears flop to either side, it may be a sign of sleepiness or sickness. It is also a typical sign of submission to a more dominant horse.

There are four major ways to estimate age of horses by appearance of their teeth:

(a) occurrence of permanent teeth,

(b) disappearance of cups,

(c) angle of incidence, and

(d) shape of the surface of the teeth.

Occurance of permanent teeth

Horses have two sets of teeth, one temporary and one permanent. Temporary teeth may also be called "baby" or "milk teeth." Temporary incisors tend to erupt in pairs at 8 days, 8 weeks, and 8 months of age.

As cups disappear, dental stars appear -- first as narrow, yellow lines in front of the central enamel ring, then as dark circles near the center of the tooth in advanced age.

The four center permanent teeth appear (two above and two below) as the animal approaches 3 years of age, the intermediates at 4, and the corners at 5. This constitutes a "full mouth."

Disappearance of cups

Young permanent teeth have deep indentures in the center of their surfaces, referred to as cups. Cups are commonly used as reference points in age determination. Those in the upper teeth are deeper than the ones below, hence they do not wear evenly with the surface or become "smooth" at equal periods of time. In general, the cups become smooth in the lower centers, intermediates, corners, upper centers, intermediates, and corners at 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 years of age, respectively. A "smooth mouth" theoretically appears at 11. A few horse owners ignore cups in the upper teeth and consider a 9-year-old horse smooth-mouthed. Although complete accuracy cannot be ensured from studying cups, this method is second in accuracy only to the appearance of permanent teeth in determining age.

As cups disappear, dental stars appear -- first as narrow, yellow lines in front of the central enamel ring, then as dark circles near the center of the tooth in advanced age.

Angle of Incidence

The angle formed by the meeting of the upper and lower incisor teeth (profile view) affords an indication of age. This angle of incidence or "contact" changes from approximately 160 to 180 degrees in young horses, to less than a right angle as the incisors appear to slant forward and outward with aging. As the slant increases, the surfaces of the lower corner teeth do not wear clear to the back margin of the uppers so that a dovetail, notch, or hook is formed on the upper corners at 7 years of age. It may disappear in a year or two, reappear around 12 to 15 years, and disappear again thereafter. The condition varies considerably between individuals, but most horses have a well-developed notch at 7.

Shape of the surface of the teeth

The teeth undergo substantial change in shape during wear and aging. The teeth appear broad and flat in young horses. They may be twice as wide (side to side) as they are deep (front to rear). This condition reverses itself in horses that reach or pass 20 years. From about 8 to 12 years the back (inside) surfaces become oval, then triangular at about 15 years. Twenty-year-old teeth may be twice as deep from front to rear as they are wide.

Abnormal teeth conditions

"Parrot mouth" is a result of the upper and lower incisors not meeting because the lower jaw is too short. This condition is rather common and may seriously interfere with grazing.

"Monkey mouth" is the opposite of parrot mouth and is seldom seen in horses.

"Cribbing" is a habit common to stabled horses which damages incisors by chipping or breaking them.

"Bishoping" is tampering with cups to make the horse appear younger than it is.

"Floating" is filing high spots in molars to facilitate chewing. Molars should be checked regularly by veterinarians as the horse approaches mid-life and should be kept floated as needed thereafter.

Definition: "Galvayne's Groove." A groove said to appear at the gum margin of the upper corner incisor at about 10 years of age extends halfway down the tooth at 15 years and reaches the table margin at 20 years. It then is said to recede and disappear at 30 years.

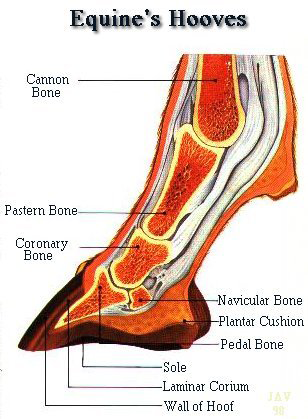

Equine Hooves

The horses hooves are extremely complex structures, very sensitive to stress and pressure and with an excellent blood and nerve supply. On the outside and underneath, they are protected by horn (a form of modified, hardened skin) which grows down from the coronet band, a fleshy ridge around the top of the hoof, equivalent to the cuticle on human nails. Inside the hoof, the horny outer structures are tightly bonded to the sensitive ones by means of leaves of horn and flesh (called laminae) which interlock around the wall of the hoof. The sensitive structures themselves surround the bones of the foot.

When weight is put on the foot it flattens and expands slightly, squashing the sensitive tissues and their blood vessels between the horn outside and the bones inside. The blood is squeezed up the leg into the veins, which have valves stopping the blood running back again. When the weight is removed, fresh blood rushes back into the tiny vessels (called capillaries) and so the process goes on.

It was thought until very recently that it was almost entirely pressure on the frog which pumped the blood around like this, but recent research has shown that, although the frog plays a part, it is the expansion of the whole foot which is important. The frog, together with the plantar cushion inside the heels, mainly helps reduce concussion on the foot.

The Need For Shoes

The hoof horn grows all the time but is worn away very quickly in a horse working on a hard surface. Horses are shod with metal shoes to prevent them from becoming footsore, but this prevents the horn from being worn down, so the farrier has to trim away excess horn at each shoeing before refitting or replacing the shoes (approximately every 4-8 weeks, depending on the rate of wear or growth).

It takes a horse an average of six months to grow a complete new hoof. Existing horn quality cannot be improved. However, a new horn can be improved by diet containing methionine, biotin, and other substances of which your vet can advise you on.

.png)

Register Now

Register Now